The Danger of the Divine

Perhaps it is baggage brought from whatever prior beliefs they had, but newer Heathens and a surprising number of older Heathens tend to perceive the Gods as kindly and approachable. The view that the Gods care about us on an individual basis and desire or are at least amenable to direct communion with us is a common one to encounter in general paganism. This is also true in Heathenry. Some will point to the Eddic poems, such as the Hyndluljóð, wherein the Goddess Freyja helps Óttar learn his lineage as proof of such relationships and the Gods’ openness to same.

In response, it might be pointed out that taking the Eddas too literally is a pitfall. For example, one theory is that the purpose of the poem was to assign a noble genealogy to Óttar Birtingr, who was assassinated in 1146. [1] Additionally, it may be pointed out that while it’s true there are examples of individuals being favored by the Gods, they are often heroes who lead tumultuous and arguably unenviable lives or that these chosen are exceedingly rare. Taking these counter arguments into account, it would seem strange that the attention of the Gods upon a single person would be thought of as ideal or even common practice.

Yet, this dance of argument and counter argument is rooted only in interpretations of the lore. There are, I believe, more convincing and edifying reasons why these attitudes about the divine should be avoided. The concept of boundaries is fundamental to the Heathen worldview, as are the related concepts of sin and thew. [2] The boundary between the innangearde and utangearde exists to protect the inner from the dangers that dwell in the outer. The crossing of these boundaries was never done frivolously; one didn’t merely saunter in to a place where a people not their own lived. The boundary between the innangearde and utangearde was guarded and had to be upheld. One might say the mutual inviolability that frið demands created a sort of boundary between prosperity and disaster within the tribe.

The same goes for how we approach the Gods. We must understand that the Gods are Holy and wholly other; they are not of our reality and exist objectively of us. To experience the Holy in earnest is to experience the ultimate paradox; we are simultaneously thrilled and terrified, exultant and humiliated. We experience a suppression of our reality in the face of a greater reality, a temporary loss of identity in the presence of the Holy. [3] These experiences are right and proper to pursue; they, along with the blessings bestowed upon the tribe are how we measure the efficacy of ritual. Proper ritual is how we communicate with the Holy, it is how we negotiate that boundary between the profane and the Holy.

There are three major dangers I’d like to point out in the assumption of open access to deity and in seeking personal relationships with them. The first is the concept of wrath. The second is the concept of “numinous addiction” and the third is the disfavor of the Gods themselves. These ideas are all interrelated and bound up within the theological concept of the Gods as numinous beings.

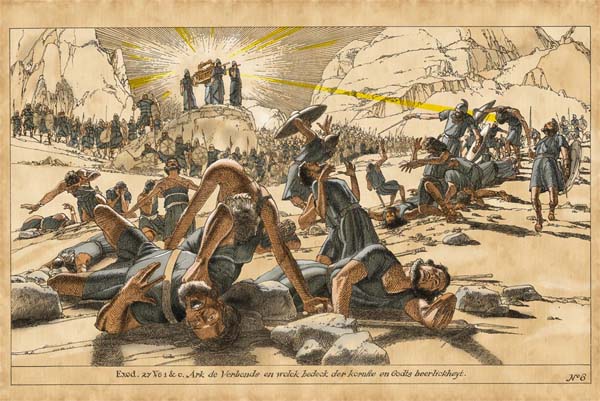

First, imagine a physical boundary as a highly electrified fence, one that doesn’t merely give us an unpleasant jolt but rather a nasty, long-lasting shock that leaves us trembling on our rear-ends. This idea in mind, we may begin to understand the kind of boundary that exists between the world of the Holy and the world of the profane. This “electric fence” was called by the Greeks “ὀργή (orgé)”, commonly translated as “wrath”. Rather than arising as a result of moral transgression, however, this wrath, like the fence in my example is indiscriminate and unthinking in zapping those who stray too close. This wrath is the overwhelming augustness of the Holy, an extension of the divine. [4] It is only abated through ritual and decorum; an opening is made in the electrified fence allowing ingress.

The second danger I refer to as “numinous addiction”, meaning the desire, often overmastering, to experience the Holy again and again and the inevitable disappointment and increased longing for “a fix”. While dread, fear and apprehension are part of the religious experience, so too are joy, excitement and ecstasy. Once we experience the divine we long to experience it again, which is only natural. Yet this desire, if left unchecked, can only serve to alienate us from our folk and to dominate our lives. An even bigger danger is the madness it risks. We are simply not wired to frequently expose ourselves to a state of being that suppresses our own reality and sense of self. While those who are mad in the lore and history have brought insights, they were, by necessity, creatures of the utangearde. The danger of disassociation from our mortal reality to the detriment of ourselves and our tribe makes this risk too great.

A related danger to this “numinous addiction” is the risk of cheapening the experience. The more compulsively we engage in something, especially something that we have both high and specific expectations of, the greater our chances of self-delusion and taking for granted the experience.

The third danger is that of earning the disfavor of the Gods. Our Gods are not omnibenevolent; indeed some of them it could be said are at best ambivalent about us. Even the Gods who are more generally considered “friendly” to mankind, such as Thunor are not so forgiving so as to ignore transgressions against them. A stranger or even a friend who rudely stands at your door and makes demands of you would quickly find themselves unwelcome on your doorstep; I believe it is no different with the Gods. While careless or ineptly performed ritual may often result in nobody on the other line, it can also risk offense and disfavor, especially when coupled with misdeeds in spaces set aside for the Holy. We ought to fear this disfavor not out of a sense of divine punishment and fear of being struck by lightning and brimstone; but rather because the worst thing we can bring upon ourselves and our tribe is to have the Gods withdraw their blessings from us completely.

An attitude of easy accessibility, of an “open door policy” with the Gods ignores their fundamental nature inasmuch as we are able to understand it. It presumes an absence of order and righteousness that does not and cannot exist within the Holy; the Gods are the source of what is right and true. Just as we have boundaries between our innangearde and that which lies beyond, it is the same for the Gods. Just as we expect guests to respect those boundaries in order to receive our favorable treatment, so to must we respect the boundaries between we the profane and Them, the Holy.

To do otherwise is dangerous.

[1] Hollander. The Poetic Edda pg. 129

[2] Autio. Sin, Thew and the Bones of Innangearde

[3] Otto. The Idea of the Holy pgs. 22-23

[4] Otto. The Idea of the Holy pg. 18